Ethics in Context: A 1908 Lexicon’s Reflection on Moral Philosophy

This article discusses the definition and understanding of the term ‘ethics’ within a historical context. However, I do not wish to delve too deeply into history, as in the case of Aristotle (born 384 BC in Stageira; died 322 BC in Chalkis on Euboea). A glance at a lexicon from the year 1908 will suffice—specifically, Meyer’s Small Conversation Lexicon, seventh edition in six volumes.

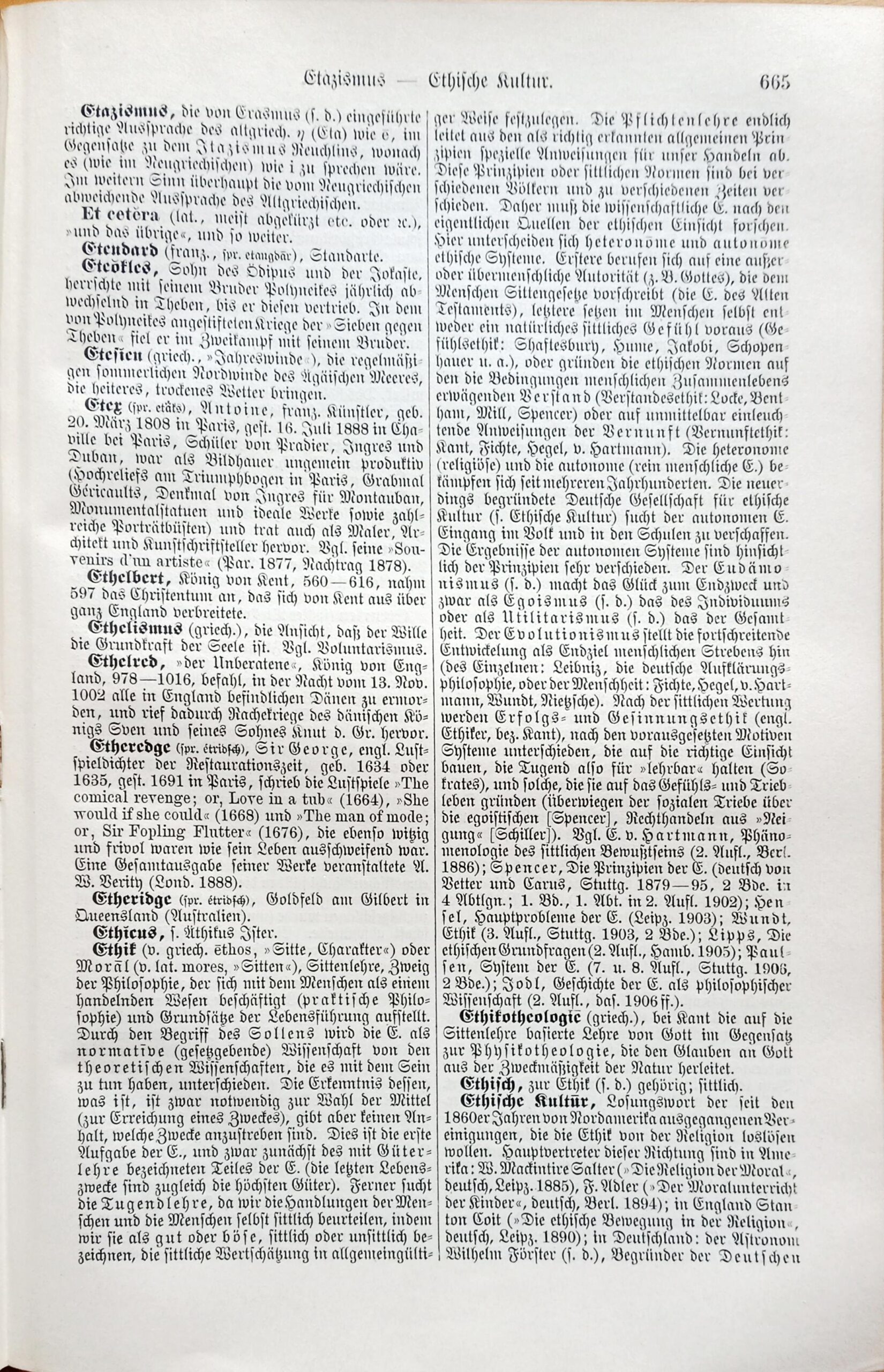

Here we have the original transcript in German. Since it is written in an outdated linguistic form as well as orthography and old German script, I have retained the text, leaving grammar and style unchanged. For the English translation, I have chosen an elaborate and formal wording, as no original source text exists.

Translation of the original text. Ethics (from Greek ēthos, “custom, character”) or morality (from Latin mores, “customs”), moral theory, a branch of philosophy that deals with humans as acting beings (practical philosophy) and establishes principles for conducting life. The concept of volition distinguishes ethics as a normative (legislative) science from theoretical sciences, which deal with being. While knowledge of what is is necessary for choosing the means (to achieve an end), it does not provide any guidance as to which ends should be pursued. This is the first task of ethics, and specifically of the part of ethics known as the theory of goods. (The ultimate ends of life are also the highest goods.) Furthermore, the theory of virtue seeks to establish moral evaluation in a universally valid manner, since we ourselves morally judge human actions by labelling them good or evil, moral or immoral. Finally, the doctrine of duty derives specific instructions for our actions from general principles recognized as correct. These principles, or moral norms, vary among different peoples and at different times. Therefore, scientific ethics must search for the true sources of ethical insight. This is where heteronomous and autonomous ethical systems are distinguished. The former appeal to an extra- or superhuman authority (e.g., God) that prescribes moral laws for humans (Old Testament ethics). The latter either presuppose a natural moral feeling in humans themselves (ethics of feeling: Shaftesbury, Hume, Jacobi, Schopenhauer, and others), or base their ethical norms on the understanding that considers the conditions of human coexistence (ethics of understanding: Locke, Bentham, Mill, Spencer) or on immediately obvious instructions of reason (ethics of reason: Kant, Fichte, Hegel, von Hartmann). Heteronomous (religious) and autonomous (purely human) ethics have been at war with each other for several centuries. The recently founded German Society for Ethical Culture (see ethical culture) seeks to introduce autonomous ethics among the people and into schools. The results of autonomous systems vary greatly in terms of their principles. Eudaemonism (see above) makes happiness the ultimate goal, namely, as egoism (see above), that of the individual, or as utilitarianism (see above), that of the whole. Evolutionism presents progressive development as the ultimate goal of human endeavor (of the individual: Leibniz, the German Enlightenment philosophers, or of humanity: Fichte, Hegel, von Hartmann, Mundt, Nietzsche). According to the moral evaluation, a distinction is made between success ethics and ethics of conviction (English ethicists, re. Kant), and according to the presupposed motives, systems are distinguished which are based on correct insight, thus considering virtue to be “teachable” (Socrates), and those which base it on the emotional and instinctual life (predominance of social drives over egoistic ones [Spencer}, righteous action out of “inclination” [Schiller}) End of original text.

Sources:

Bgl. Ethik v. Hartmann, Phänomenologie des sittlichen Bewußtseins (2. Aufl. Berl. 1886);

Spencer, Die Prinzipien der Ethik (Deutsch Better and Janus, Stuttg. 1879 – 95, 2 Bde. in 4 Abtlgn.; 1.Bd., 1 Abt. in 2. Aufl. 1902);

Hensel, Hauptprobleme der Ethik (Leipz. 1903);

Mundt, Ethik (3. Aufl., Stuttg. 1903, 2 Bde.);

Lipps, Die ethischen Grundfragen (2. Aufl., Hamb. 1905);

Paulsen, System der Ethik (7. u. 8. Aufl., Stuttg. 1906, 2 Bde.);

Jodl, Geschichte der Ethik als philosophischer Wissenschaft (2. Aufl., Das. 1906 ff.).

A Conclusion in a more Modern Language: This lexicon entry from 1908 offers intriguing keys to understanding ethics. Here are some notable aspects:

Ethics as Practical Philosophy: The text highlights ethics as a discipline concerned with humans as active beings and their way of life. Unlike theoretical sciences, it examines normative principles and volition.

The Tripartition of Ethics:

- Doctrine of Goods: What should the highest aims of life be? It revolves around selecting objectives and the ultimate goods to pursue.

- Doctrine of Virtue: Moral actions are evaluated, and universal standards for such judgments are sought.

- Doctrine of Duty: Specific guidelines for actions are derived from general ethical principles.

Heteronomous vs. Autonomous Ethics:

- Heteronomous Systems: Ethics is derived from external authorities (e.g., God).

- Autonomous Systems: Ethics is anchored within humans themselves, whether through feelings (feeling-based ethics), reason (reason-based ethics), or rationality (rational ethics).

Ethical Diversity and Conflicts: The various systems, such as Eudaimonism (goal: happiness), Utilitarianism (goal: common welfare), or Evolutionism (goal: development), demonstrate the breadth and disagreement among ethical principles. Similarly, there is the conflict between religious and autonomous ethics.

Moral Evaluation of Actions:

- Ethics of Intention: Actions are judged based on motives and attitudes (e.g., Kant).

- Ethics of Consequences: Actions are evaluated based on their outcomes.

- Teachability of Virtue: Differentiation between Socrates’ concept of “insight” and approaches rooted in emotions and drives (e.g., Spencer, Schiller).

Philosophical Sources and Development: The text references significant works and thinkers such as Kant, Hegel, Fichte, and Schiller, who have further developed ethics.

Summary: The lexicon entry provides a comprehensive historical perspective on ethics as a science and the diversity of its approaches. Ethics and morality are evidently topics that have preoccupied humanity for a very long time. However, they must demonstrate flexibility and adapt repeatedly to new circumstances. The demands in various aspects of life can indeed differ and also prove challenging. Nevertheless, this historical example helps to better understand certain fundamental principles.

Pingback: Ethik im Kontext: Reflexionen eines Lexikons von 1908 zur Moralphilosophie – Poschacher International Ltd